This description has been translated and may not be completely accurate. Click here to see the original

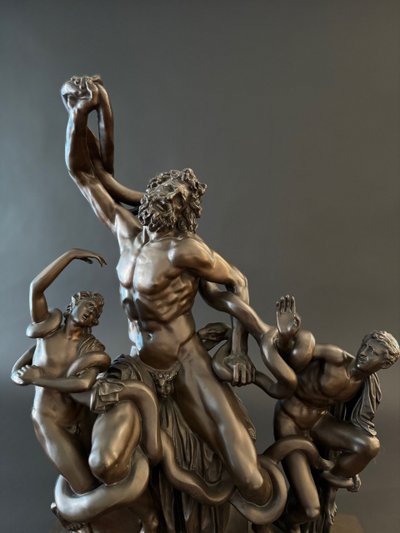

Important patinated bronze group depicting Laocoön and his sons trapped by Neptune's serpents.

In the center, between his two sons, the athletic Laocoön desperately fights to save his two sons' lives and his own from an unjust and cruel death.

One of the two serpents, rising from the ground, sinks its fangs into the body of the youngest, already dying, his head tilted back, while his father struggles to avoid the same fate.

The three protagonists have their limbs bound in a complex network of powerful reptile knots. We can see the swollen and tense muscles of Laocoön, who has reached the limit of his strength. All this under the terrified gaze of the second son, a helpless witness to his father's tragic death.

Good condition, beautiful medal patina (brown glaze).

Small traces, uncleaned bronze.

F. BARBEDIENNE. FOUNDER. , signed on the base, confirming a 19th-century cast (while "Barbedienne fondeur, Paris" indicates an early 20th-century cast).

Numbered in ink on the back 3201

A bit of history

Laocoön, a priest of the cult of Apollo, had, against the will of his protector, married and had children.

While the Greeks offered a huge wooden horse to the Trojans for their protector Athena, Laocoön urged them not to let him in. He is said to have thrown his spear at the horse's flanks.

At the same time, while the horse was performing a sacrifice to Neptune on the shores of the Aegean Sea, Apollo (who had not forgotten the insult) sent two monstrous serpents to the surface of the waves to kill his two sons. When Laocoön tried to rescue them, they killed him too by encircling him in their coils. The two reptiles then took refuge at the feet of the statue of Athena.

The Trojans, unaware of the secret life of their priest Laocoön, misinterpreted Apollo's anger: the priest had been punished for degrading the offered horse. The gods actually wanted to make it clear to them that they should let the horse in. Which they did.

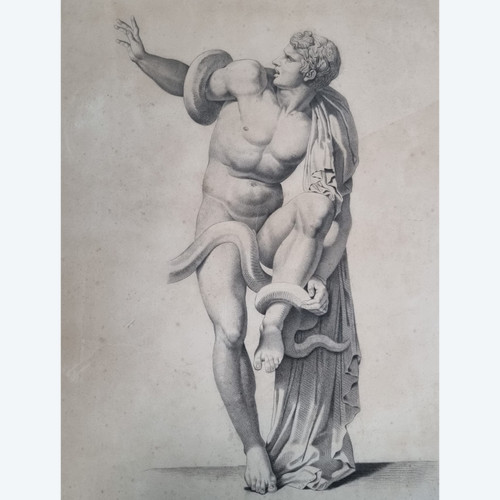

The ancient Roman marble group of Laocoön has been a source of inspiration for the past 500 years. It probably remains the most famous of all ancient sculptures, through which generations have been able to reflect their own struggles.

The fascinating exhibition "After the Antique," presented at the Louvre in 2001, explored the multiple inspirations for Laocoön. One of the most extraordinary is the engraving by Niccolo Boldrini, made around 1545, less than 50 years after the group's discovery, which shows the protagonists as apes. Titian's involvement and the actual meaning of the print have been, and remain, much debated, but the power of visual metaphor is intensely striking. Over the centuries, the Laocoön has been used countless times in political parodies and inspired artists from Rubens to Max Ernst. More recently, the Jordanian illustrator Emad Hajjaj has brought the Laocoön's relevance to the present day with his striking drawing of Laocoön and his sons battling a coronavirus. The image continues to be a powerful symbol.

References and Bibliography

A. Pasquier, "Laocoön and His Sons," in D'après l'antique, exhibition, Musée du Louvre, 2001, pp. 228-273;

F. Haskell and N. Penny, Taste and the Antiqe. The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900, New Haven and London, 1981, pp. 243-247, no. 52;

P. Fogelman, P. Fusco & M. Cambareri, Italian and Spanish Sculpture. Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collection, Los Angeles, 2002, pp. 250-256, cat. 32;

French: F.G. Brewer, D. Bourgarit and J. Basset, 'French Bronzes (16th-18th Centuries): Notes on Technique' in G. Bresc-Bautier, G. Scherf and J. Draper (eds.), Cast in Bronze. French Sculpture from Renaissance to Revolution, exhibition cat. Musée du Louvre, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009, pp. 28-41;

. G. Scherf, “French Bronzes in the 18th Century,” in G. Bresc-Bautier, G. Scherf & J. Draper (eds.), Cast in Bronze. French Sculpture from the Renaissance to the Revolution, exc. cat. Musée du Louvre, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2009, pp. 364-371;

P. Malgouyres, “Apollo and Daphne, and Other Bronze Groups after Bernini,” in J. Warrend (ed.), Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in and around the Peter Marino Collection, London 2013, pp. 68-83

Ref: LWBIDB4F7X