This description has been translated and may not be completely accurate. Click here to see the original

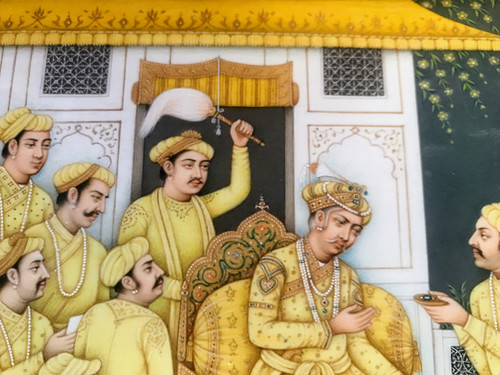

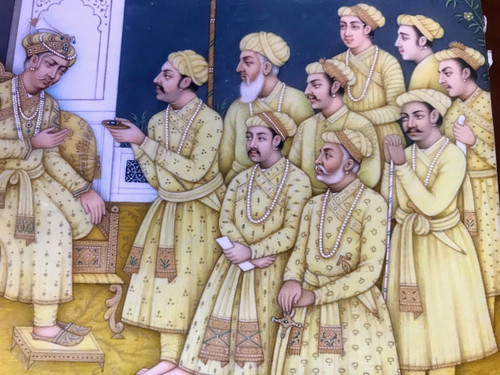

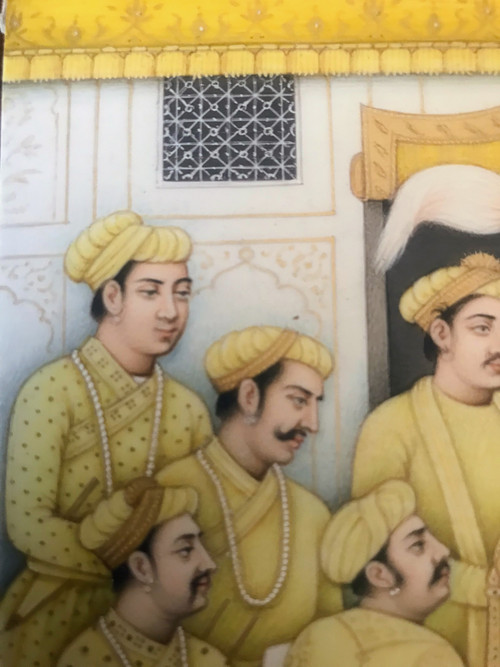

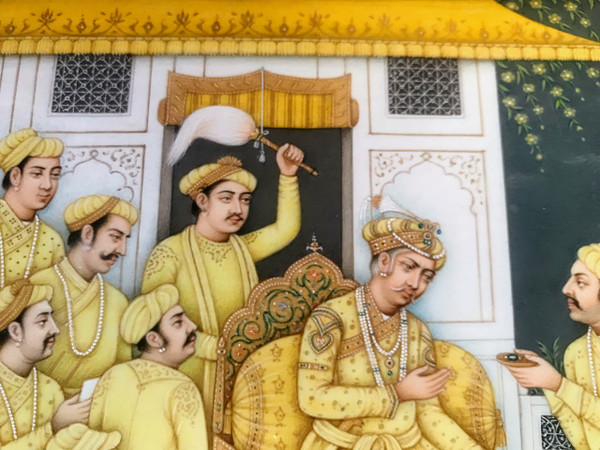

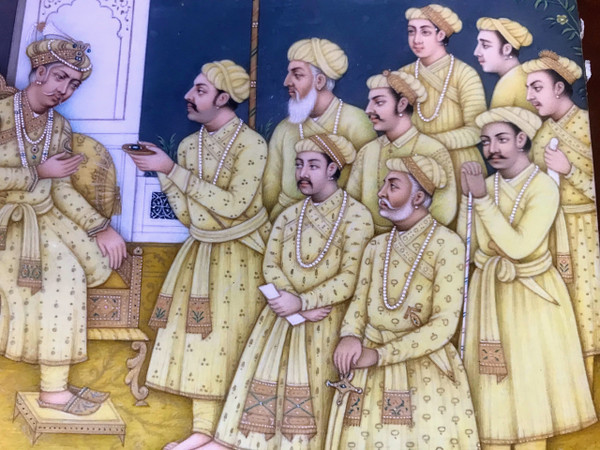

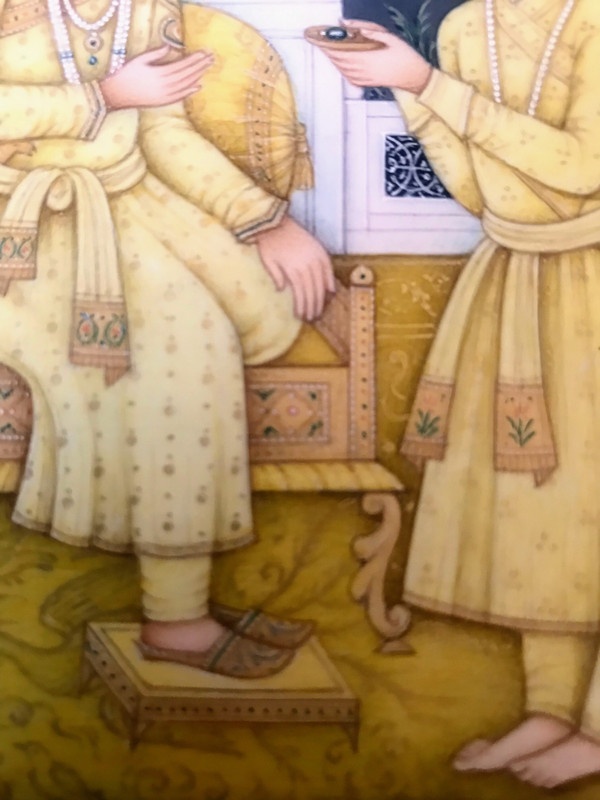

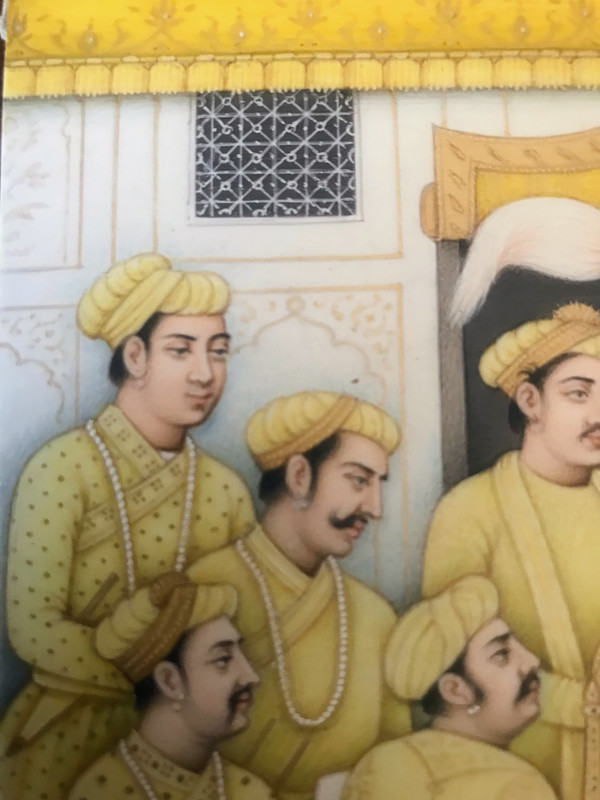

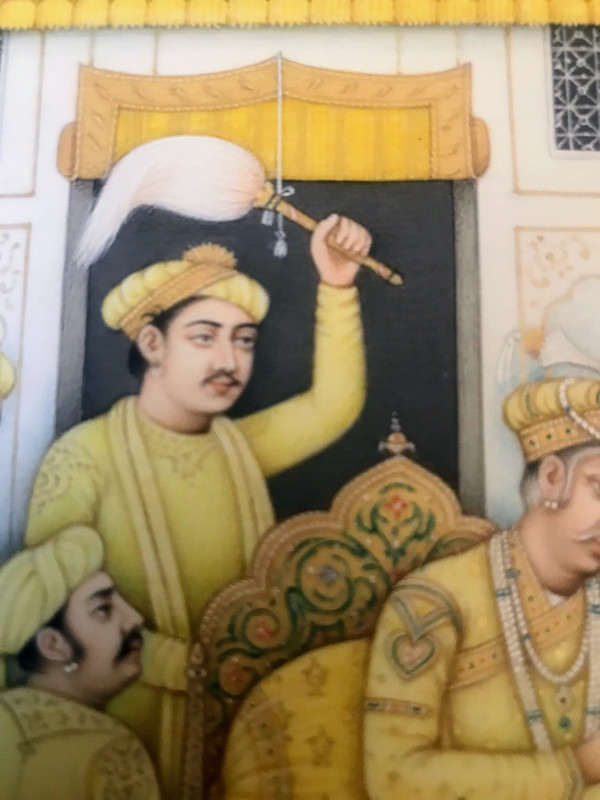

Mughal miniature of remarkable finesse, each face of each of the characters having its own expression, painted on a large plate, it represents the Emperor Akbar the Great enthroned on a terrace, surrounded by his court and receiving a delegation of dignitaries offering him a jewel (probably an emerald).

19th century or older.

dimensions of the plate: 21.5 cms x 14.5 cms

We offer this miniature with only a protective glass. Depending on your wishes, we can offer you a very high quality frame, traditional or design.

This sovereign left a considerable imprint on the history of India during his half-century of reign.

He promotes a religious syncretism, the Dîn-i-Ilâhî, which leads him to great religious tolerance, and to the reform of both Muslim and Hindu law.

He had an extremely important influence in the Arts and notably created his imperial workshop of miniatures, overturning the canons of the time and of which our miniature is a fine example, particularly in terms of the representation of faces in profile and their individual expression.

"...When Emperor Akbar (1556-1605), who from childhood showed a pronounced taste for painting, set up an imperial workshop, he entrusted its management to two Persian masters, Mir Sayyid 'Ali and Abd us-Samad, whom his father Humayun had taken into his service when he was in exile at the court of Shah Tahmasb. During the first years of his reign, Akbar was especially seduced by the imaginary and the fantastic and the imperial artists illustrated, at his request, the manuscripts of the Hamza-name, the story of the legendary life of an uncle of the Prophet, the Amir Hamza, or even of the Tuti-name, the popular Tales of the Parrot, so popular in the Eastern world.

However, around 1580, the emperor's attraction to the fabulous diminished and his interest shifted to history. He ordered the writing and illustration of historical works, such as the Tarikh-i-Alfi, annals of the Muslim world during the first millennium, and the famous Akbar-name, chronicle of the reign. This taste for history aroused in the emperor an acute curiosity for historical figures and quite naturally led him to favor the art of the portrait as a privileged means of apprehending the personality of an individual. Abul-Fazl, biographer and friend of Akbar, recounts, in the A’in-i-Akbari, the original decision of the emperor to create an album of portraits: “His Majesty himself posed for his portrait and also ordered that the portraits of the great characters of the kingdom be executed.

Akbar wanted his painters to capture the personality of their models; he thus deliberately goes against the rules of Islamic orthodoxy rigorously prohibiting the representation of the human figure and thereby affirms his independence in matters of religion: "Many are the men who hate painting; I do not like these men. to feel that it is impossible for him to confer an individuality on his work, and he is consequently compelled to think of God, who alone bestows life. Thus he increases his knowledge."

In the very first portraits designed during Akbar's reign, the influence of Persian masters dominates. The Safavid tradition transmits its precious character and its sense of shimmering colors, its search for decorative effects, its taste for slender and ethereal silhouettes. The portrait, under Akbar, is primarily decorative and offers an idealized image of the subject. The lasting Persian imprint is revealed in the stereotyped appearance of the characters, with faces that are both impersonal and conventional. But a slow Indianization of the human figure gradually develops: the look and proportions of the figures change and Persian grace gives way to an increasingly conscious taste for volume.

The heads, hitherto almost invariably depicted in three-quarters following the Safavid tradition, are replaced by faces most often depicted in profile.

This gradual freedom from Persian aesthetics goes hand in hand with the discovery and assimilation of European techniques and models. As early as 1510, in fact, the Portuguese had established themselves on the western coast of India, after Alphonse of Albuquerque (1453-1515) had taken Goa from the Sultan of Bidjapour. In 1579, at the request of Akbar, a Jesuit mission went from Goa to the court, in order to participate in the religious discussions organized by the emperor in the Ibadat-Khana or House of Adoration. The missionaries brought the emperor

Ref: ELWQCCJXBJ

Empire mahogany desk 19th century

7.500 € EUR

Empire mahogany desk 19th century

7.500 € EUR

Gold Bracelet With Micro-Mosaic Medallions

1.900 € EUR

Gold Bracelet With Micro-Mosaic Medallions

1.900 € EUR